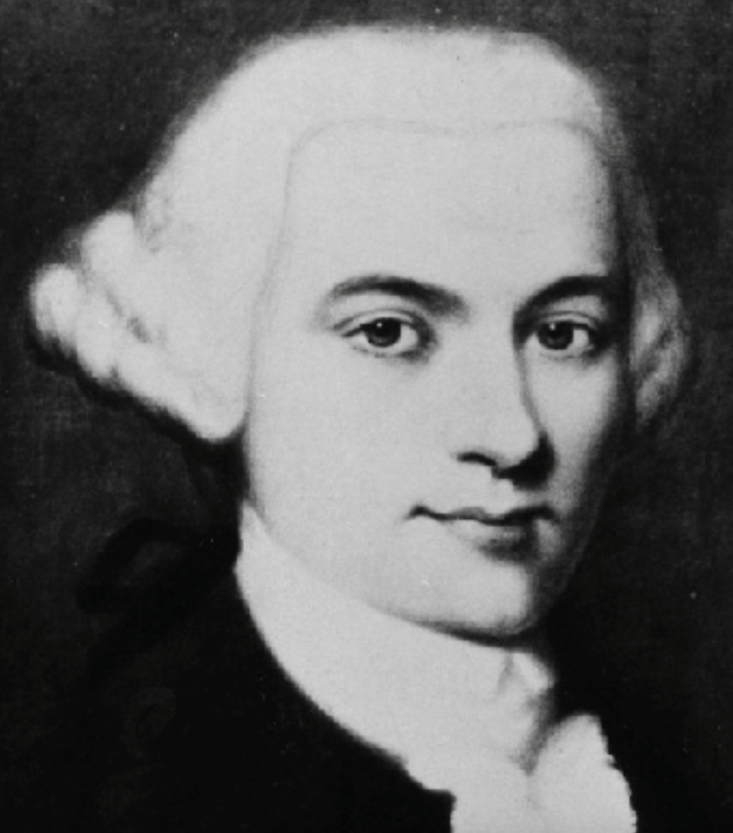

Thomas Percival

Thomas Percival (1740-1804) MD FRS SA: Physician Extraordinary. A true polymath – physician and philosopher; moralist and ethicist; Dissenter and slave-trade abolitionist. Social reformer working for improved public health and factory regulation. Devised the first modern code of medical ethics. Founder of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society.

Thomas Percival is one of the the earliest known residents of Hart Hill. He took the house in 1775, for the purpose of health and for the pleasure of occasional retirement.’ He lived there for less that 10 years but was probably the most intellectual and influential occupant the house has known. Its environment was at once restful and inspiring for the hard-working doctor and writer, and must have been an idyllic playground for his growing family.

Early life and education Much of what we know about Thomas Percival’s personal and family life is told to us by his son Edward, who wrote in 1807, Memoirs of the Life and Writings of Thomas Percival. Born in Warrington on 27 September 1740, he was the youngest son of Joseph Percival and Margaret Orred, and the grandson and nephew of physicians. It was not a wealthy family, but Edward Percival felt that, ‘The slender fortunes of this line were compensated by intellectual endowments and hereditary worth’.

Thomas was orphaned at the age of three when both parents died within hours of each other. His own childhood health was later described by his son as, ‘feeble and precarious’. He was raised by his eldest sister and supported by his physician uncle, also called Thomas, who died when Thomas was 10 years old, leaving him a valuable library and a love of learning.

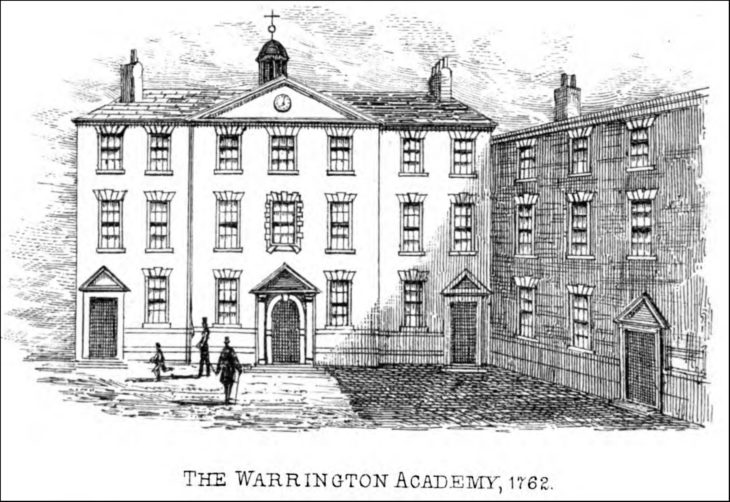

His family had left the Church of England and Thomas became the first pupil at the newly established Warrington Academy for the sons of Dissenters. There he developed a keen interest in ethics, theology and philosophy but was barred, as a Dissenter, from attending Oxford or Cambridge. Thomas went to Edinburgh University where he studied Medical Science, and then on to Leyden in Holland where he qualified as MD in 1765.

Whilst at Edinburgh Thomas became firm friends with Thomas Butterworth Bayley of Hope Hall, who became ‘foremost among the number of his intimate friends and companions’ . In 1767 he moved to Manchester with his young wife and son and lived there and in Hart Hill, Pendleton for the rest of his life.

Family life Thomas and his wife, Elizabeth Bassnett, had at least 11 children. His son Edward explains that Thomas adopted as his motto a sentiment of Cicero, ‘What more and better service could we make to our country than to educate and train the youth?’ He certainly put this principle into practice during his first summer at Hart Hill, when he wrote the first volume of , ‘A Father’s Instructions; consisting of moral tales, fables and reflections…’ for his children. The introductory note includes:

‘In our delightful retirement at Hart Hill, everything around me has conspired to suggest ideas of your health, your happiness or improvement. The setting sun, the shady tree, the whispering breeze, or the fragrant flower have alike furnished some tale or anthology which has been applied to your instruction…..’

His daughter Anne (known as Fanny) was to marry Nathaniel Heywood and was the mother of Sir Benjamin Heywood, 1st Baronet Claremont. Her descendants have had a significant influence on the development, land use and road names in Pendleton ever since.

Public health In the early 1770s Thomas Percival studied the population and death rates across Manchester and surrounding areas. His results showed mortality rates of 1 in 28 in Manchester compared with 1 in 120 in rural Monton, just four miles away. He proposed ways of collecting more accurate population and mortality statistics and corresponded with Benjamin Franklin, one of the founding fathers of the USA, on the value of censuses.

His early work on the impact of epidemics on the health of working children influenced Sir Robert Peel’s factory reforms. The deaths from ‘Hooping-cough’ in May 1780 of two of his youngest children can only have strengthened his resolve to tackle the causes and spread of infectious diseases through improving living and working conditions and medical provision.

In 1789 and 1795 typhus and typhoid epidemics hit Manchester. As a surgeon at the Manchester Infirmary, he worked with like-minded colleagues to study the living conditions of the working classes of the town and recommend reforms. In 1795, he was instrumental in establishing the first voluntary Board of Health which worked to prevent the generation and spread of infectious diseases and to shorten and alleviate the sufferings of those affected.

The isolation of patients with infectious diseases was a priority for Thomas, and this was achieved first by establishing ‘Fever Wards’, designating 25 beds in four houses on Portland Street, Manchester. These were replaced in 1803 by a purpose built 100 bed ‘House of Recovery’ on the site of the Infirmary, later occupied by the Grand Hotel on Aytoun Street.

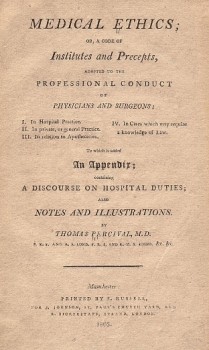

Medical Ethics Probably the best known of Thomas Percival’s works is his 1803 groundbreaking ‘Medical Ethics; or a Code of Institutes and Precepts adapted to the professional conduct of Physicians and Surgeons.’ His last major work, this was the first codification of its kind and covered hospital settings, private and general practice, apothecaries and cases requiring knowledge of the law. The code began as an attempt to arbitrate the difficult relationships between the various medical practitioners at the Manchester Infirmary. It was a set of rules and regulations which surgeons, physicians and apothecaries were to follow in their dealings with each other and their patients. It was probably the first use of the term ‘medical ethics’. The work influenced the codes of practice eventually adopted by the British and American Medical Associations

Scientific experimentation Thomas Percival’s writings and letters reveal a man committed to advancing scientific knowledge for human benefit. He investigated the medicinal uses of ‘Fixed Air’ (Carbon Dioxide) by testing its effect on plants and animals. Hart Hill proved to be the ideal location for some experiments. In 1778 he sent fellow scientist Joseph Priestley samples of the air from both central Manchester and Hart Hill. Priestley’s analysis concluded that the air quality at Hart Hill was ’nearly the same as that of Wiltshire.’

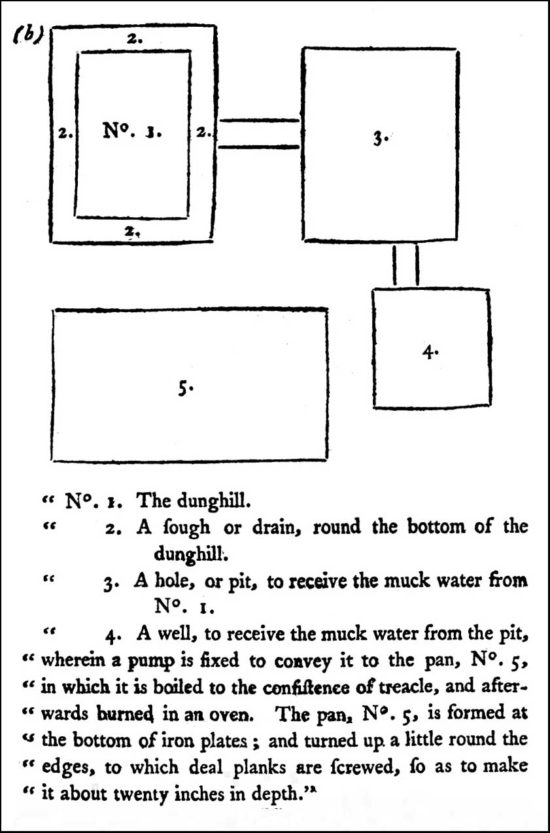

In 1780, in an essay on cheaper methods of producing the fertiliser potash, Thomas described his experiments in making compost from ‘dung-hill water’:

‘At Hart Hill, my summer abode three miles from Manchester, I have lately practiced a method of making a compost of the dung hill water. The weeds and rakings of the garden, the dressings of the fields, the leaves blown from the trees, and other refuse matters, are put together near the reservoir, out of which the water is occasionally pumped and scattered over the heap; so strong a ferment almost instantly excites putrefaction. And these vegetable substances are soon converted into a fertile mould, which retaining the salts and oils of the dung hill water, suffers the superfluous moisture to exhale into the air or to percolate through it. And I have found by experience, that the compost thus prepared is laid on the meadows at less expense, and that it is more efficacious and durable in its operation than the sprinklings which at stated times, they formerly received: for my land, though good and in fine condition, is light and sandy’.

Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society Whilst living at Hart Hill Thomas Percival hosted the first meetings that gave rise to the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society (the Lit. & Phil.). Around 1780, according to his son Edward, Thomas started weekly meetings for the purpose of conversation, ‘at his own house…the resort of the literary characters, the principal inhabitants and of occasional strangers…’ As these gatherings grew in numbers, the group moved first to a tavern and then formally constituted itself as a Society, with Thomas elected first president, a post he retained jointly or solely until his death.

In 1784, during these years with the Lit. and Phil., Thomas published his Dissertations, which give us a flavour of the breadth of his knowledge and interests in addition to medicine and science. The subjects covered included:

- On Truth and Faithfulness

- On habit and Association

- On Consistency of Expectation in Literary Pursuits

- On a Taste for the General Beauties of Nature

- On a Taste for The Fine Arts

- On the Alliance of Natural History, and Philosophy with Poetry

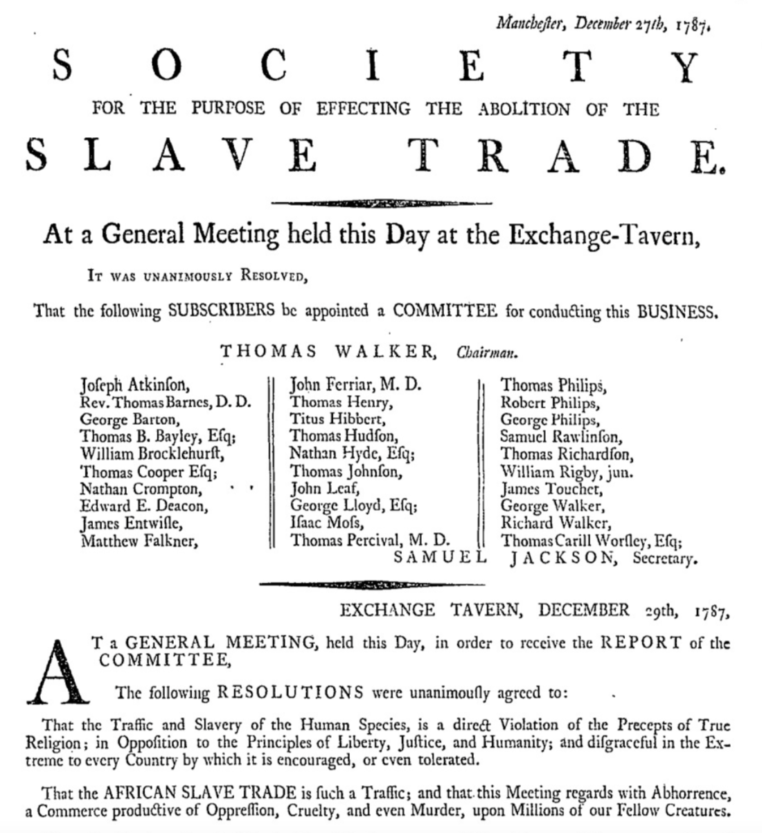

Members of the Lit. and Phil. were typically Dissenters and radical reformers. In the mid 1780s many of its members were involved in establishing the Manchester Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, of which Thomas Percival was a prominent and active member. The Lit. & Phil. still thrives today with around 400 members.

On his death, the Society installed a tablet (below) in his memory, written by his friend and colleague Thomas Henry.

Later years Whilst still at Hart Hill, Thomas became afflicted with a painful and debilitating eye condition, which he attributed to his common practice of reading and writing while travelling around in his carriage. The condition was chronic and forced him to have constant assistance in all his work. It may have been for this reason that he eventually left Hart Hill in 1783 and returned to living full-time in Manchester.

He had kept a town house in Manchester throughout his working life, first on King Street (where he was a neighbour and friend of Samuel and Hannah Greg of Quarry Bank Mill), and later at 7, Mosley Street, where local City Directories had him listed in 1800.

He died in 1804 of rheumatic fever, and despite having been a Dissenter for most of his life, he was returned to Warrington and interred at the local parish church St Elphin’s, where there is an epitaph commemorating him.

Thomas Percival’s will and legacy. At the time of his death Percival was living at 7 Mosley Street, Manchester, then the most fashionable street in the town. Percival’s will reveals considerable material assets comprising ‘land, messuages and tenements situate in the County of Lancaster’. These, including a leasehold estate in Warrington, were left in the care of his three trustees; son in law Nathaniel Heywood, Rev Thomas Barnes and Thomas Robinson, esq. The trustees were at liberty to rent or sell these assets and to invest the money in public funds to provide income for his wife and children. The will also reveals that Percival was financially astute, successfully investing capital in stocks which reaped returns. Several amounts of money were left for the benefit of his sons including £500 for Stanley Orred Percival’s apprenticeship to ‘fit him for trade and business’. Elizabeth Percival was to receive 400 guineas per annum from the interest from her husband’s Irish and American investments. She also received all of her husband’s household furniture and his stock of wine and liquors. Percival’s three surviving daughters, Fanny, Margaret and Eliza were each left £400, the profits of his investment in the ‘Loyalty Loan’ taken out in 1797. Percival’s library was left in the care of his son Edward Cropper Percival from which Elizabeth was allowed to choose 200 items for her own personal use and that of the family. There were several codicils to the will which made minor bequests to family members including money for mourning clothes on his death. Perhaps the most historically significant codicil, however, was the appointment of his son Edward Cropper Percival and Jabez Bunting to examine his personal papers, manuscripts and letters after his death and ‘preserve or destroy’ what they thought fit. Many of the letters later appeared in The works, literary, moral, and medical of Thomas Percival (1807). The 600 pages reveal much about Percival including his efforts to improve public health, his support for the abolition of slavery and the importance of statistical returns in advancing understanding and improvement of social conditions. This early advocacy of data collection was to be advanced by two of Percival’s descendants. Grandson Benjamin Heywood was a founder member of the Manchester Statistical Society which still operates. Just over 100 years after Percival’s death great-great granddaughter Isabel Mary Heywood established the Manchester and Salford Blind Aid Society but not before she had gained a thorough statistical understanding of the extent of the problem.