Fairhope and the Hope Park Estate

Fairhope was a large, imposing house, one of a group of high quality residences built from the early 1850s at Hope Park, Eccles Old Road. Previously farmland, Hope Park was originally part of the Hope Hall estate. Fairhope and Hope Park are closely associated with the rising fortunes of the Agnew family and in particular Thomas Agnew snr (1794-1871) a print seller and art dealer with galleries in Manchester, Liverpool and London. Agnew initially acquired 3.5 acres of the Hope Estate around 1847 on which he built several residences, including Fairhope.

In 1836 a series of adverts appeared in the Manchester press signalling the initial development of the land to the west of Hope Hall, then in the ownership of the Hobson family. In March 1836 the Manchester Guardian announced:

Hope Estate – various parts of this beautiful estate are now on sale for building purposes and will be disposed of in chief rents to suit purchasers. Sites, equal if not superior to any in the neighbourhood, are to be met with on the property and to persons wishing to build within 3 to 4 miles of Manchester: such an opportunity seldom occurs. The prospect from the higher parts of the estate is very extensive and ranges over a country free from annoyances almost inseparable from the vicinity of a town like Manchester. Details and plans available from Mr Atkinson architect Store Street and Samuel Taylor surveyor Cooper Street Manchester.

This advert probably prompted interest in the site from the Manchester Proprietary School. Involved in the early discussions about the school Samuel Brooks, a Manchester banker, landowner and developer of Whalley Range, was appointed an inspector of the three prospective school sites. Clearly seeing the potential of the Hope Park location for high quality residences Samuel Brooks purchased the land at Hope with alacrity. Meanwhile, whilst an alternative site at Didsbury was chosen for the Manchester Proprietary School the venture failed to raise the £40,000 share value and appears to have been abandoned.

In mid July 1836 a further notice appeared in the Manchester newspapers: HOPE PARK—To builders, road makers and others desirous of contracting for the several works required in the erection of the lodge and for the forming, making and fencing of the several roads, may see the plans and specifications at the offices of Mr. Lane, Architect, St. Ann’s-street, Manchester.—Tenders to delivered on before Monday, the 1st August next.

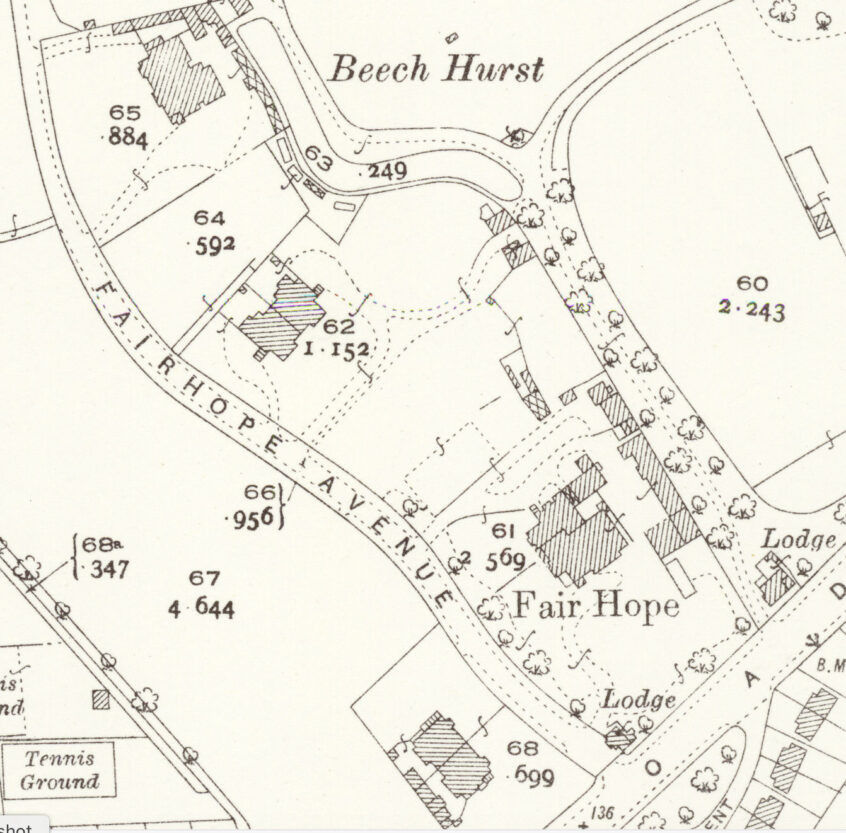

It seems likely that this is the road clearly evident on the 1848 ordnance survey and subsequent maps, The road has been re-named over the years. Initially named Beauchamp Place the road and later known as Hope Avenue and Fairhope Avenue, the latter remains its name to this day.

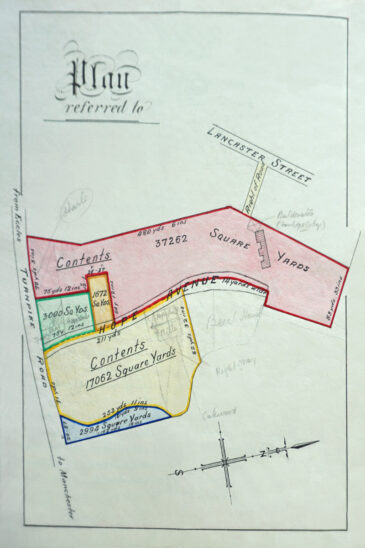

Soon after acquiring land at Hope Samuel Brooks released a plot of land of 17,062 square yards to John Hayward for houses of a rental value of £142.3s.8d. For unknown reasons this release was transferred to Richard Lane and Thomas Agnew snr. Negotiations must have taken place between Lane and Agnew as at a later date, probably 1847, Agnew became the sole owner of the 17,062 square yards, the location of his future home known as Fairhope and several other high value residences which included Hopefield, Oakwood, Fairleigh and Hopelands.

Samuel Brooks laid down some exacting conditions on the buildings and land use at Hope Park. Houses were to ‘be built in a proper and workmanlike manner in all respects and with good materials of every requisite description and shall be of brick or stone or both to be set in lime mortar and with good oak or fir timber and covered with good slates and shall be when finished of the clear yearly letting value of £80 at the least.‘

‘No messuage shall be converted into two or more dwellings for the time being. Each shall have a frontage of 12 yards at least and be placed 20 yards backwards at least from the north easterly side of the new road and no outbuilding other than boundary walls shall be erected on the said land nearer than 50 yards of the new road. No spring or water course shall be diverted and shall continue as its usual course.’

‘Thomas Agnew and his heirs will leave open and unbuilt upon so much of the said land and will not permit any steps or other projections on the said land to extend into the new road or impede free passage thereof. Thomas Agnew must lay with good and substantial Rochdale flags three inches thickness at least and space of 6 feet wide and on proper and uniform level all along the south easterly end of the said new road. At the outer edge of this flagged pavement good and sufficient kerb stones. The road to be paved according to the Macadam system or with good gravel to the middle of said new road.‘

‘to provide convenient and sufficient drainage of land and buildings and pay half towards the main sewer and drain under the road. Thomas Agnew to pay half the maintenance of the sewer and the part of the road that abuts his land.’

‘Thomas Agnew and his heirs and tenants shall not erect or carry on any steam or fire engine, vitriol works, glass works, copper works, brass foundry, dye house, bowking house, stove printing works cotton factory or slaughter house or the business of a smelter of fat, fustian dresser, pipe maker, tallow chandler, retailer of wines beers or spirits or fermented liquors. No manufacturing trade, business or employment whatsoever or any public nuisance or private inconvenience…………….and provide a wall, hedge or other good and sufficient fence and maintain it in good and proper order.‘

In July 1873 the executors of Samuel Brooks sold a further ‘parcel of land of the Hope Estate’ to John Heelis, a land surveyor and son of Stephen Heelis of Halton Bank. Amounting to a single acre, the land cost £806 13s 4d and had similar conditions attached to earlier houses including erecting no more than two houses, keeping them in good condition, having a letting value of no less than £100 and requiring submission of plans for approval before construction. The building was to be at least 15 yards from Beauchamp Place with its main frontage to the road and with perimeter walls no higher than 4 feet without railings.

This house was Beech Hurst which became Heelis’s main home for several years but was later the residence of Thomas Chester Ansdell and his wife Constance (nee Agnew) and their two children Thomas Agnew Ansdell and Beryl Constance. Beech Hurst had seventeen rooms

In 1874, After the death of his father, Thomas Agnew jnr (1827-1883) added to Agnew land at Hope Park by purchasing adjacent farmland, perhaps in reaction to the building of Beech Hurst and developments on Brooks land along the western side of Lancaster Street (later Lancaster Road). Referred to as Fairhope farm on census returns this land was relatively untouched by housing development until the building of the Fairhope Council Estate in the 1940s.

In 1883 Thomas Agnew jnr died leaving his considerable wealth, including the Hope Park estate, to his son Lockett. Thomas’s widow Anne, continued to live at Fairhope until her death in 1906 whilst her son Lockett, now a senior member of Agnew’s dealership on Bond Street, increasingly based himself in London. Sometime before the advent of the First World War the Hope estate became the property of the Ansdell family. It was Thomas Chester Ansdell who lent Fairhope to the British Red Cross.

British Red Cross Hospital During the First World War Fairhope became a Red Cross Auxiliary hospital. Details about the hospital can be found In An illustrated account of the work of the Red Cross’s East Lancashire branch during its first year :-

Fairhope a commodious dwelling house kindly lent by T. Ansdell esq was opened as an Auxiliary Home Hospital on November 11th 1914 by the Pendleton Branch of the British Red Cross………….surrounded by a sheltered and well-wooded ground, and having a southerly aspect it has proved to be eminently suitable for the purpose of a hospital……….. full opportunity for outdoor recreation and concerts and entertainments are arranged.

Internally there were six wards, dining rooms and a kitchen and staff rooms. Originally the provision was for 20 wounded servicemen which eventually rose to 35. The wounded, of British, Australian, Canadian and Belgian origin, were suffering in the main from bullet, shrapnel wounds and frost bite.

The hospital was run by a Voluntary Aid Detachment with a committee comprising a Chairman, medical officers and lady superintendents. The hospital received a government grant but was additionally dependant on subscriptions and donations from the public which also included furniture, beds and bedding. Red Cross records reveal that many local people contributed their time and skills. Go to https://vad.redcross.org.uk/Search?hosp=fairhope to find out about those who volunteered at the Fairhope Auxiliary Hospital during the First World War. The records reveal the names and addresses of volunteers, hours spent supporting the wounded and their tasks.

We know little about those receiving treatment at Fairhope but one of the wounded was a local man John Hurdley:-

AFTER 21 YEARS’ SERVICE. Company Sergeant-Major J. HURDLEY (155), Battalion Manchester Regiment of Brindle Heath Road, Pendleton. For conspicuous gallantry on 4th June on the Gallipoli Peninsula. During assault he was wounded in the head and partly paralysed, but refused to be taken to the rear, and continued to give orders and rally scattered parties in the Krithia Nullah. It was largely due to his brave conduct that the advanced line was held. Company Sergeant-Major Hurdley, who is now in the Fairhope Red Cross Hospital, Pendleton, is probably the tallest man in his battalion, standing considerably over six feet. His extreme height proved unfortunate, however, for he was shot at the top of his head. He has no fewer than 21 years’ service to his credit, as he served years the Shropshire Light Infantry before joined the old Manchester Regiment (now the 6th Manchesters) in 1897. He received his promotion to company sergeant-major in “0” Company (late Captain H. B. Pilkington), on the reorganisation of the battalion under the double-company system when they went Egypt. Before mobilisation he was employed as a draughtsman by Messrs. Pilkington at Clifton Junction. Manchester Evening News – Thursday 16 September 1915

As far as we know John Hurdley returned to civilian life and had a long and productive career. His medals appear to have been sold at a later date to an unknown buyer.

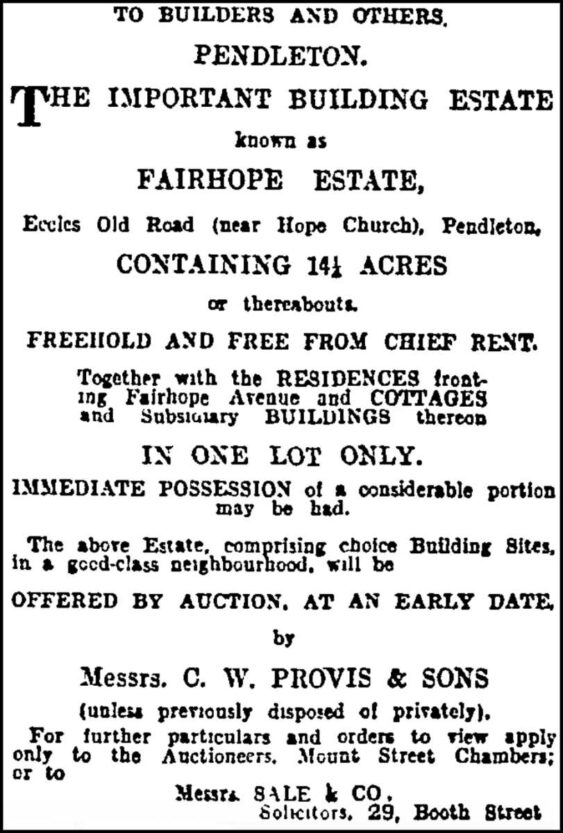

Fairhope ceased to be a Red Cross hospital at the end of the war and from 1921 to 1926 the house was occupied by caretakers. Agnew family members finally severed their connection with Hope Park, now known as the Fairhope Estate, in 1926 when Thomas Agnew Ansdell and Beryl Constance Leese put the estate on the market following their father’s death (left). The land then passed into the hands of John Lomax Prestwich before being sold in 1946 by J. P. Hill Ltd to Salford Corporation. The Corporation built the Fairhope housing estate providing 185 houses and the United Kingdom’s first residential smoke free zone. After one hundred years Agnew’s Hope Park estate was swept away. Only one historic building survives today: the semi-detached houses originally known as Fairleigh and Hopelands which served as NHS offices before being converted into apartments.