James Dugdale

James Dugdale of Hart Hill (1813-76) was a Lancashire cotton manufacturer, merchant, businessman, landowner and art collector. Around 1859, whilst living at Higher Bentcliffe, Eccles, Dugdale bought the Hart Hill estate next to Buile Hill where he built an impressive mansion. Dugdale amassed great wealth from his business interests ending his life as a gentleman farmer in Warwickshire where he became the High Sheriff. James Dugdale and Mary Louisa Plummer (1830-1895) were married in 1854. They had nine children.

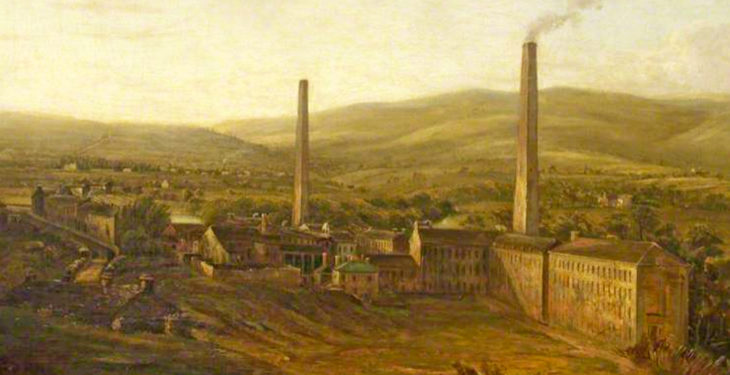

James Dugdale was born into a family of cotton manufacturers and calico printers of Lowerhouse, Padiham, near Burnley. The business, established in 1797 by his grandfather Nathaniel Dugdale (1761-1816), was expanded by Nathaniel’s three sons John, James and William operating as Dugdale Brothers. Nathaniel’s stock book reveals that by 1800 the Dugdales owned 24 jennies and two carding engines producing spun yarn which was distributed to handloom weavers across the Burnley area, including Crawshawbooth, Huncoat and Padiham. Dugdale Brothers diversified and expanded the business, establishing block, plate and roller printing processes at Lowerhouse with a warehouse in Manchester, accumulating assets of £76,229 by 1824. They also invested in land and buildings in central Manchester.

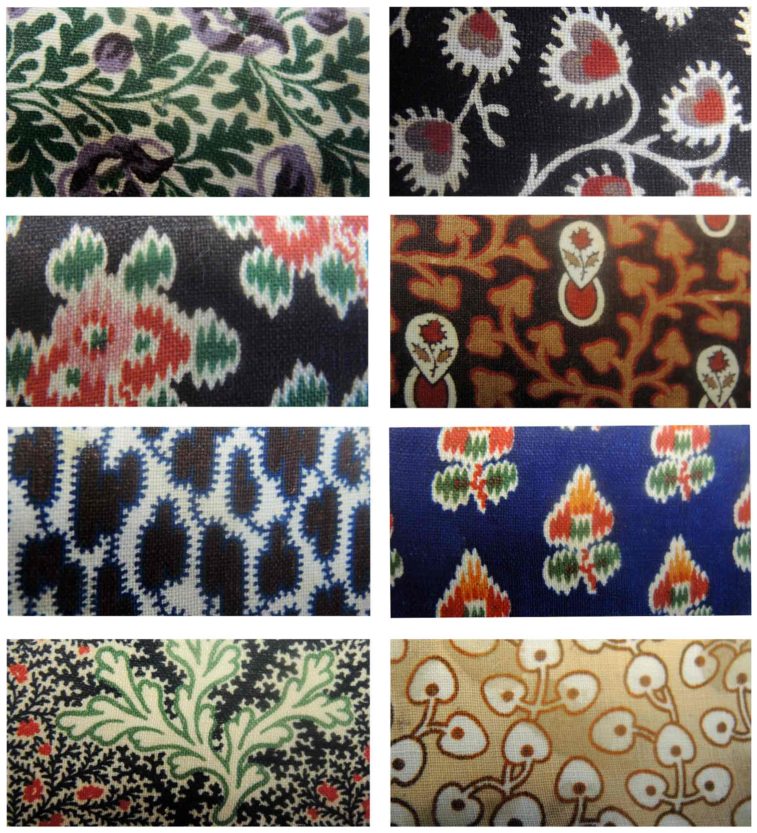

The Dugdales of Lowerhouse Initially cotton spinners, who ‘put out’ warps to local weavers, Dugdales diversified their business in response to consumer demands and fluctuations in trade at home and abroad. From the early 1800s a wider range of dyestuffs, made possible through advances in chemistry and the invention of cylinder printing machines, resulted in high volume production of printed calico. What had initially been a luxury cloth available to the wealthy and fashionable elite was now accessible to all levels of society. The Dugdales took advantage of the many advances in printing and dyeing, developing block, plate and roller printing at Lowerhouse from the 1820s whilst continuing to spin yarn and commission cotton cloth.

By 1835 cheap printed cotton had dropped to 4d a yard and a dress could be made for 2s 6d bringing it within the reach of large numbers of the population at home and abroad. By 1846 Dugdales had eight cylinder-printing machines, seventy block printers working 120 tables, five steam engines and a waterwheel at Lowerhouse Mill. When printed textiles went out of fashion in favour of plainer woven designs Dugdales responded by increasing their spinning and weaving operations. By 1891 they had nearly 75,000 spindles and 1531 looms predominantly producing cloth for the Chinese market.

As well as owning a large mill complex, part of which survives, the Dugdales built 108 houses and cottages, a gas works, co-op shop, and chapel for their workers at Lowerhouse. On the face of it, they would appear to be benevolent and paternalistic employers. However in 1842 a Parliamentary Commission revue of the implementation of the 1831 Truck Act revealed that the Dugdales of Lowerhouse might have been flouting the law, charging their workers inflated rents and requiring them to buy goods from the company’s shop above the normal price. To provide milk and meat for their company shop Dugdales kept a farm at nearby Huncoat. The parliamentary revue also revealed the harsh system of fines in place at Lowerhouse. ‘Young Mr Dugdale’, perhaps James, comes out of the enquiry particularly badly as he is accused of beating a worker for a very trivial offence and extracting heavy fines.

The Dugdales in Salford Whilst James Dugdale continued to live near the family mill at Lowerhouse, Burnley at the time of the censuses in 1841 and 1851, his father John had established his home in Salford close to his warehouses on Cannon and Market Streets in Manchester. John Dugdale (1786-1855) married Mary Marshall from Manchester in 1809. They moved from Accrington to Salford after the births of their six children, including sons James (b.1813) and John (b.1822). Baines Directory in 1825 shows John Dugdale living at Richmond Hill in Salford, then a fashionable address. He also owned Dovecot House in Knotty Ash, Liverpool.

Owd Stink o’ Brass James’ father John Dugdale was for many years known locally as ‘Owd Stink o’Brass’. In 1835 he unsuccessfully challenged Joseph Brotherton for the Salford Parliamentary Seat running under the Conservative ticket. It was during this election campaign that he was heckled by a voter about his wealth, to which he retorted ‘Ay, I fairly stink o’ brass’, giving rise to his subsequent nickname. Shortly afterwards, John moved to Irwell Bank on Eccles New Road where he was recorded in the 1841 census, with his second wife, Elizabeth and son John (born 1822). He died at his Liverpool home, Dovecot in 1855. Son John was still living at Irwell Bank in the mid 1850s when his older brother James was his neighbour at Higher Bentcliffe House. James’ eldest son, James Broughton Dugdale was born there in 1855, the year before Thomas Trueman decided to sell the old Hart Hill house and adjoining estate.

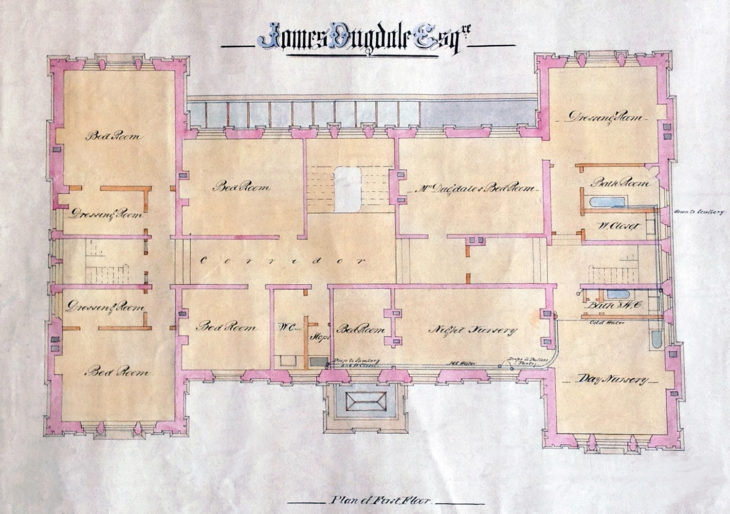

Pendleton James Dugdale certainly saw the business potential of land on the Eccles Road, then still predominantly undeveloped and yet ‘only three miles from the Exchange’ in Manchester. In 1838 James Dugdale placed an advert in the newspapers proposing to set up an association to buy 20 acres of the Hope Estate for building villas. His scheme coincided with the death of Elizabeth Hobson of Hope Hall and it is possible that the land was in the vicinity of Weaste Lane or perhaps further down the Eccles Road at Gilda Brook. When the Hart Hill estate became available in 1856 Dugdale bought ‘the quaint old-fashioned stucco house’ which he demolished, replacing it with a grand mansion to the design of the architect Walter Scott of Liverpool. To date no images of the second Hart Hill of 1859 have come to light but we do know that the house was built in the ‘Elizabethan style’. Plans of the house show it to be a large symmetrical stone built house, confirmed by two recent archaeological investigations. In 1861 Dugdale cemented his standing in the neighbourhood as a major benefactor to the new church of St James, Hope where he was probably influential in the choice of Scott as architect.

Baths and laundries James Dugdale’s business interests were wide and varied. In 1854 he was one of a group of Manchester businessmen, including Thomas Bazley, William Fairbairn and Elkanah Armitage, who founded the Manchester and Salford Baths and Laundries Company. In its first year the Company announced profits and a dividend, a position which continued for two decades. Amongst the four baths and laundries built by the company three were designed by the celebrated architect Thomas Worthington. Only one of the four baths remains; Worthington’s famous Greengate Baths (Grade II*) built in 1855 but now derelict and awaiting restoration (above left). When it opened on August 27th 1856, at a cost of £9,913, it was considered one of the finest pools in the country and became a model for later municipal baths and wash houses.

‘SALFORD BATHS AND LAUNDRIES. These neat and commodious baths and laundries are so far advanced towards completion that it will not be premature to give some description of them. They are situated in Collier-Street, Greengate, Salford, and are erected by the ‘Manchester and Salford Baths and Laundries Company,’ which, an inscription on the front of the building states, was incorporated in 1855. The site of the building is where stood the Salford Old Workhouse, now demolished and numbered with the things of the past, its place being occupied by what is regarded by sanitary reformers as an establishment for lessening the need for pauper houses, by promoting personal cleanliness and all the temporal advantages which are likely to result from the practice of the virtue which the proverb says is “next to godliness”. The building erected for the Salford Baths and Laundries is a neat and commodious structure of brick and stone, tasteful in its design, and well adapted to its purpose, the ornamentation being simple and effective, often serving economical use in the object of the building, and consequently inexpensive. The architect is Mr. Thomas Worthington, King Street, Manchester. Manchester Courier 26 July 1856

Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition Dugdale was a financial contributor to the exhibition held in 1857, donating £1,000 towards the fund and becoming a commissioner. The catalogue of loans to the exhibition reveals a number of artworks belonging to one J Dugdale Esq. Several of these were also exhibited at the 1862 exhibition in London. Dugdale’s art collection requires further investigation but we know that he owned two significant paintings by Augustus Egg, The Life of Buckingham and The Death of Buckingham which he bought around 1870, both now in the Yale Centre for British Art.

Move to Wroxall In 1861, just a few years after building Hart Hill, James Dugdale bought the 2,000-acre Wroxall Abbey estate in Warwickshire for £93,000. Hart Hill became James Dugdale’s ‘winter residence’ for a short time until the house was sold to Thomas Hornby Birley in 1864. The Wroxall estate, the site of a monastery and church, had once belonged to Sir Christopher Wren. Dugdale continued to amass a considerable personal fortune which he invested in his art collection, restoring the ancient estate chapel and engaging Walter Scott to design a new, but much larger, mansion in the Gothic Revival style. Eventually becoming High Sheriff of Warwickshire he died in 1876 leaving effects to the value of £350,000 and was interred at Wroxall Church.

Dugdale owned the companion paintings The Life of Buckingham and The Death of Buckingham (above) both painted in 1855 by Augustus Egg and bought by Dugdale around 1870. Both these paintings are now in the Yale Center for British Art.

James Dugdale’s final will reveals the extent of his wealth including his paintings, bronzes, marbles, plate and silver and the considerable bequests to his three sons and six daughters. Land holdings at Dovecote, Liverpool, inherited from John Dugdale, were left to his two younger sons and his widow was provided with a sum of £3,000 per annum in addition to £20,000 to provide a home for herself and their unmarried daughters once her eldest son reached 25. Meanwhile she was to reside at Wroxall with full access to all its amenities and conveniences. Their son James Broughton, the eldest of the Dugdale’s nine children, inherited the estate and followed his father as a gentleman farmer dying at Wroxall in 1927. A girl’s school from 1935 to 1995, Wroxall (below) is now a hotel and conference centre.