Louis Schwabe

Louis Schwabe (1831-1922) was a yarn merchant, shipping agent, long-standing member and Freeman of Manchester Royal Exchange, Governor of the Royal Manchester Institution and Vice-president of Manchester Art Gallery.

Family background Louis Schwabe was born in Manchester in 1831. His father, also named Louis (1798-1845), had moved to Manchester from Dessau in Germany in 1817 to make his living initially as a merchant and exporter, but later becoming a pattern designer and silk manufacturer in the booming textile industry. Louis may have converted from his Jewish faith before leaving Dessau; his brother Philip had joined the Lutheran church in 1819 naming his son Gustav Christian. Whenever Louis’ conversion occurred, he was married in1825 at St John’s church in Manchester to Eliza Steele alias Thackery. Louis and Eliza’s four children were all later baptised at St Ann’s Anglican church in Manchester.

In the early 1830s Louis Schwabe senior had business premises in Cross Street and in Henry Houldsworth’s Portland Street Mill in Manchester. The artistic designs and high quality of his woven fabrics gained him a reputation and increasing prosperity. In 1826 the Schwabes rented a house in Grosvenor Street for £20 a year but by 1838 they had moved to a substantial property at Plymouth Grove at a rent of £90.

Immersing himself in the cultural life of Manchester Schwabe was a subscriber to the Royal Manchester Institution and was involved in the founding of the Manchester School of Design in 1838, where he advocated the importance of drawing. Many acknowledged his artistic abilities and creativity. William Cook Taylor, in The Hand Book of Silk, Cotton and Woollen Manufactures (1843), wrote ‘The richness and beauty of the patterns surpass all that the imagination could previously have conceived: the flowers wrought into the silks and satins appear more like the work of the best painter than of the weaver.’

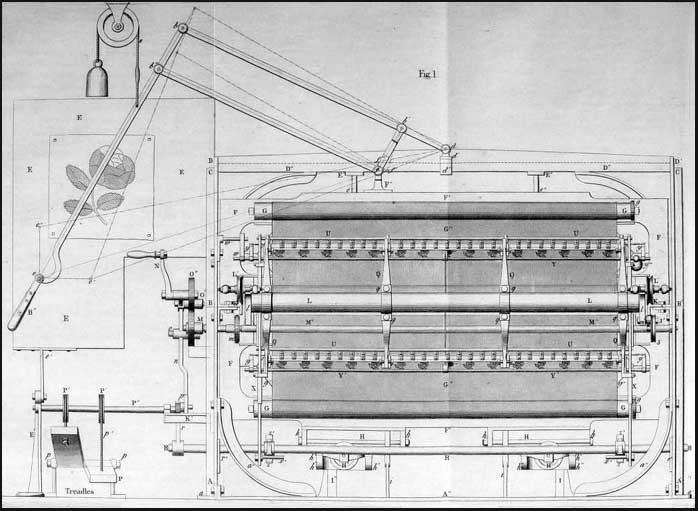

In 1839 Queen Victoria commissioned Schwabe to produce a dress of embroidered silk, which he described as, ‘unique’ and ‘by far the most costly work ever done at my establishment’. His talent for design encompassed machines as well as fabrics; he worked closely with Houldsworth on improving the design of silk looms and experimented with printing warps, a technique which later became highly fashionable and was known as ‘chine’. In 1842 Schwabe demonstrated what is thought to be the first instance of spinning molten glass through a spinneret foreshadowing the production of synthetic fabrics in the twentieth century. In the early 1840s his Manchester premises was visited by King Frederick Augustus of Saxony who witnessed a demonstration of Schwabe’s hand embroidery machine which was the first to be used in Britain. Schwabe’s developing expertise and understanding of manufacturing resulted in an appearance before a parliamentary select committee on the silk industry in 1832.

In January 1845, Louis’ father, Samson Benjamin, died in Dessau. The news had a profound effect on Louis leading to his suicide on 11 January when he poisoned himself by drinking sulphuric acid. Eliza was left a widow with three children, Rosalie, Louis and Eliza, then aged fifteen, fourteen and twelve. An obituary in The Gentleman’s Magazine stated, ‘Mr. Schwabe possessed a high taste in art, and was, to some extent, practically an artist, applying the knowledge he possessed to the purposes of manufacture – hence the great superiority and perfection of his designs, and showing in his own case (if any proof were needed) how necessary is a practical knowledge of the ‘Art of Design’ to the higher branches of manufacture.’

In his will, the elder Louis left around £2500 plus a Life Assurance policy worth £5000, to be divided between his wife and three children. After a lengthy legal battle the insurance policy was declared void because of Louis’ suicide but the company agreed to refund all premiums plus interest amounting to £9692.

Louis rises to the challenge. Louis Schwabe junior recalled visiting the Exchange with his father as a ten year old but it is not known how he acquired the business acumen that was to lead to a lucrative career in commerce. One can only surmise that his father’s reputation and family and business connections were influential during the early years of his career.

Contribution to arts and culture Having inherited his father’s hereditary subscription to the Royal Manchester Institution, Louis maintained his governorship throughout his life. He held the post of Treasurer for many years and was elected to the Vice-Presidency in 1918. Louis continued to support Manchester institutions favoured by his father and was involved in fostering cultural links to his German heritage. He was one of the founders, with Charles Halle and Emil Reiss, of the Schiller Anstalt in 1859. This club of European emigres and English middle class liberals housed a large library and reading room in Manchester and hosted literary and musical events. Fifty years later in 1909, Louis was still an active member of the club when it celebrated its 50th anniversary and was visited by Count Metternich, the German Ambassador.

Whilst Louis himself has left no evidence of artistic talent, members of his family followed artistic careers. Reference was often made to the artistry of his father’s textile designs. Louis’ eldest son, 25 year old Henry Thackeray, was listed on the 1891 Census as an ‘Art Student’ (painting)’, although he did not pursue a professional career as a painter and later censuses record him farming in Cheshire. Louis’ cousin’s son, Randolph Schwabe, who had been born in Barton-upon-Irwell in 1885, was an accomplished painter, etcher and draughtsman. He worked as a war artist in both world wars and taught for many years at the Slade School of Art. From 1938 to his death he was Slade Professor of Fine Art at the University of London.

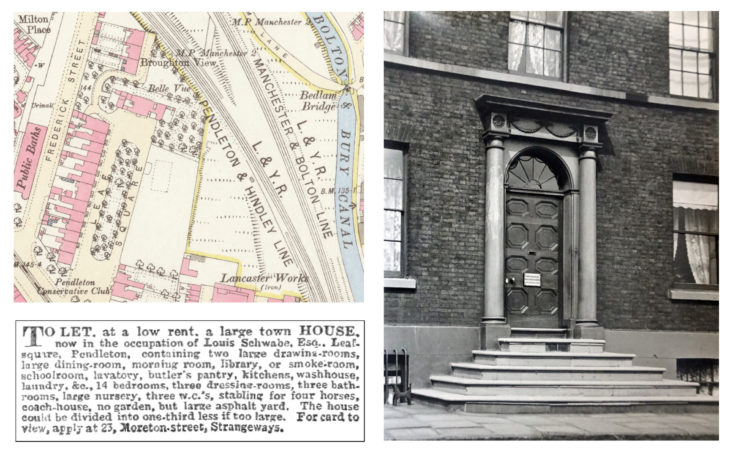

Zill & Schwabe Throughout his commercial career Louis Schwabe was linked with that of Herman Zill. By 1854 they had gone into partnership as importers of cotton yarn and later exporters of machinery. The business thrived, importing yarns and exporting twist cotton to Europe, East India, China and Japan from premises in Dickinson Street and Cooper Street in Manchester. Other business premises included Tanners Lane in Pendleton and a warehouse at Moreton Street in Strangeways.

Leaf Square Whilst Louis Schwabe jnr spent his long professional life immersed in the commercial and cultural hub of Manchester, he lived in just two areas of Pendleton for over 60 years. Sometime after Louis Schwabe senior’s death the family moved to 4 Leaf Square, Pendleton, then a genteel area of Georgian town houses built around 1805. In 1861 Louis was living there with his two sisters Rosalie and Eliza, their mother having died the previous year.

In 1864 Louis married Elizabeth Blanche Hartwright, daughter of a Stretford merchant. By 1871 the growing family had moved along Leaf Square to No.7. They now had three children, Henry Thackeray, Louis Gustav and Constance Blanche. Although both Louis and his wife had been christened in Anglican churches, all their children were baptised in the Cross Street Unitarian Chapel in Manchester.

Louis’ two sisters were still living with them in 1871 with five servants supporting the household. Over the next ten years the family continued to grow. In 1881, with five children under 16 years of age, two sisters and six servants, the Schwabe household was occupying both numbers 6 and 7 Leaf Square. Louis described himself as a Merchant. The Schwabes continued to live at Leaf Square until 1886 when Louis let the house (above), and moved to Hart Hill with his wife Blanche and family.

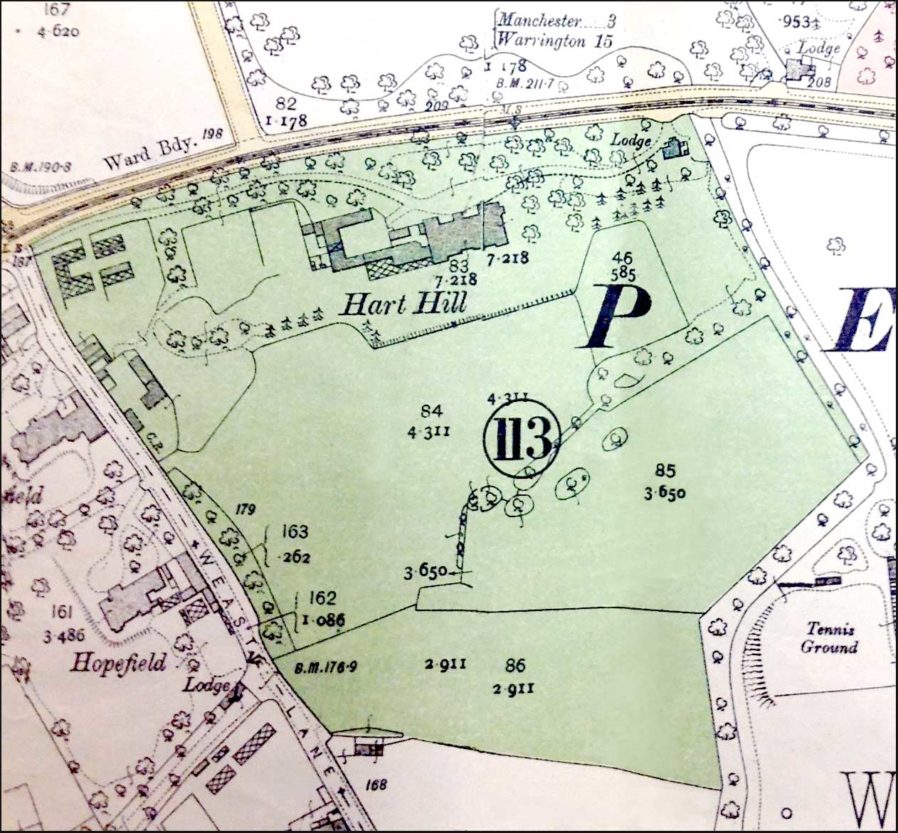

The Schwabes at Hart Hill Louis’ cousin, Gustav Christian Schwabe, had married Helen, daughter of John Dugdale of Irwell Bank on Eccles New Road in 1842. Helen’s brother, James Dugdale, bought the Hart Hill estate in 1855 and proceeded to rebuild the old house in 1859. Through family connections Louis would certainly have been familiar with the impressive new property which he would later make his main home from 1886 to 1922.

After the death of Thomas Hornby Birley in early 1885, Hart Hill came onto the market for the first time in 20 years. It must have been an ideal solution for the large Schwabe family and Slater’s Directory for 1886 shows Louis living there, with his older sister Rosalie close by at 6, West View on Lower Seedley Road. The Schwabe’s seventh child, George Boustead Schwabe had been born in 1883; their last child, Dorothy Mildred, was the only one to be born at Hart Hill, in 1886.

By the time of the 1891 Census the family was at its largest. One child, Arthur Percy, had died as a young child in 1879, and Clifford, aged 16 was training as a ‘gentleman apprentice’ at the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast (the Schwabes and Wolffs were related by marriage). The remaining five children were all unmarried and living at home. We know that Hart Hill had 33 rooms (excluding bathrooms) but even with a total of 18 occupants it would have felt very spacious with its additional 22 acres. A house and family of that size required a large number of staff including a butler and a footman from Nottinghamshire, a groom and a housemaid from Derbyshire, a nurse from Cornwall, a kitchen maid from Gloucester, a housekeeper from Chorley, a housemaid from Yorkshire and a cook and a laundress from Manchester. The staff were a typically diverse group from across the country, attracted by the prospect of work in the homes of the expanding upper middle class of businessmen and industrialists.

In the summer of 1891 Louis’ eldest daughter, Constance Blanche, was married at St Luke’s Church in Weaste. Her husband was an Eccles Old Road neighbour, Dr Alexander Stewart, a Scottish GP living at South Bank, close to the corner with Sandy Lane. The couple later moved across the road to Holly Bank, where they were still living 20 years later.

The Schwabe’s son, Louis Gustav, married a German-born British citizen Evelyn Mathilda May in 1895. They too lived at 13 Eccles Old Road in the house known as Belmont until 1902 when it became (and remains today) the Pendleton Bowling Club.

By 1901 the Schwabes had just three children still living at Hart Hill. In 1909, Louis’ youngest son, George Boustead Schwabe, died aged 26. His death certificate, signed by his brother-in-law Dr Alexander Stewart, shows that he died whilst in a diabetic coma. He was buried in Monton Unitarian Church.

The smaller family retained a staff of 10 including the butler, John Bingham Housley. John had been born 1847 in Nottinghamshire, but had moved north with his mother as a youth. We find him in 1871 at Greenheys Lane in the Hulme/Moss Side area of Manchester, a servant in the household of Sidney Potter, a calico printer. By 1881 the 33 year old had worked his way up to a butler’s post and was living in Withington, married with two young children. At the next three censuses, 1891, 1901 and 1911 he was resident at Hart Hill, working as butler to the Schwabes. What happened to his young family? John may have lived at Hart Hill much of the time, but his family were not far away and he clearly was still part of their lives. In 1901 his wife Annie, by now with five children was living at 26, Mode Wheel Road, Salford and in 1911 she is recorded at 500, Eccles New Road, less than a mile from Hart Hill. The 1911 census also showed that they had had seven children during their 34-year marriage, two of whom had died. When John retired (possibly in 1922 after both Eliza and Louis Schwabe had died and Hart Hill was sold) he lived the rest of his life at 500, Eccles New Road. His wife died in 1924, leaving John £347.8s.11d. By the time John Bingham Housley died in 1936 aged 87 he left just £94.8s.3d. – not a lot to show for a lifetime of service to the wealthy families of Manchester and Salford.

The end of Hart Hill A year before Louis Schwabe’s death a short article appeared in the Manchester Evening News which serves as his epitaph:

The Oldest member Mr Louis Schwabe, of the firm of Zill and Schwabe, Lid., yarn merchants, is recognised as the oldest living member of the Manchester Royal Exchange. Ninety years of age he is wonderfully hale and hearty, his chief grievance being that he doesn’t like feeling ‘done up’ after he has walked a couple of miles. Mr. Schwabe has been a member of the Exchange for nearly 68 years. ‘I was born in Manchester.’ he said to an Evening News representative, ‘ and my father first took me to the Exchange counter when I was ten years old. I was given a free Exchange pass after being a member for 60 years, but I gave up active participation in commerce eight years ago. Public life never appealed to me. I just attended to my own business. ‘Ah, yes! Fifty years ago the Germans were gentlemen but the events of recent years decided me, and I am stepping out of the fray.’

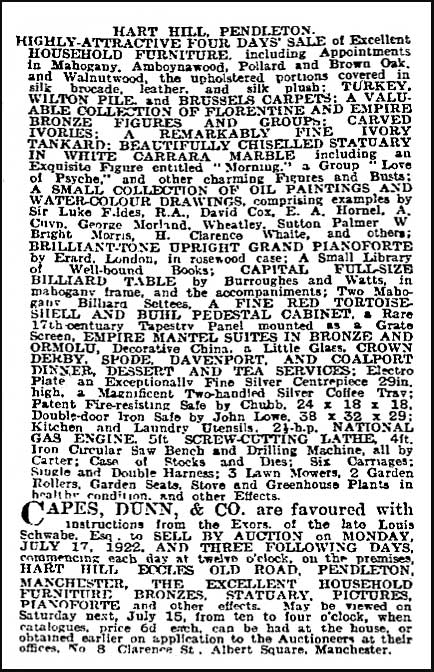

Louis’ wife Elizabeth Blanche died in 1921. Louis died the following year on 30 April 1922, aged 90. He was buried with his wife and son at Monton Unitarian Church. Less than two months after Louis’ death, auctioneers Capes, Dunn and Co. announced a four-day sale of Hart Hill’s contents. His estate was valued at £323, 826. 19s 11d.

After a legal battle the 22 acre Hart Hill estate and house were purchased by Salford Corporation in 1925 and eventually amalgamated with Buile Hill Park in 1938. The house was judged to be surplus to requirements and was soon demolished but not until Hart Hill’s Robin Hood boiler was removed to Salford parks department for service in the greenhouses at Buile Hill.