Medicine and medical science

From our early records of the residents of Eccles Old Road to the regional significance of Salford Royal Hospital today, medicine and medical science have featured throughout the road’s history. Since the last quarter of the 18th century, long before the Salford Union Infirmary was built, some of Salford’s and Manchester’s foremost surgeons and medical practitioners settled around Eccles Old Road. Several were members or founders of medical dynasties, being the descendants and / or parents of another generation of doctors and nurses.

Medical training in Manchester and Salford

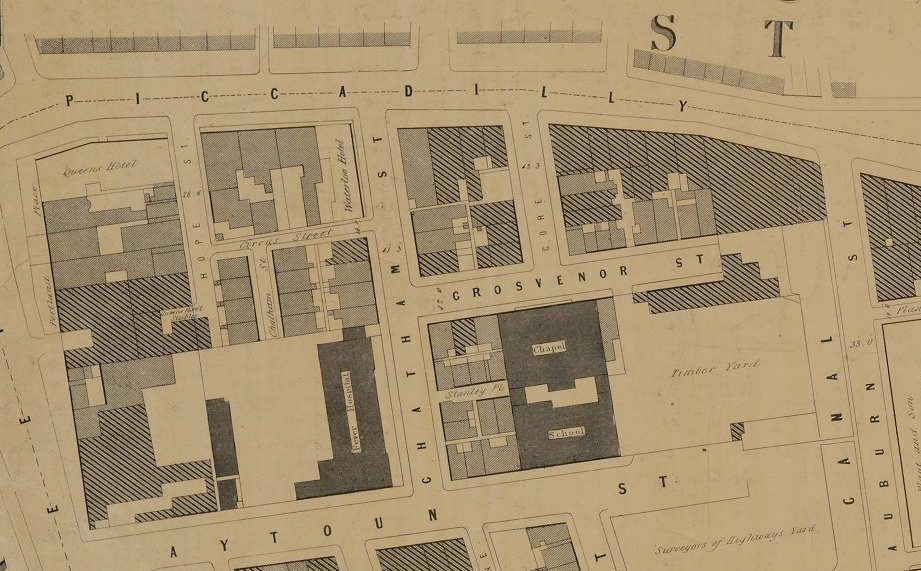

The first English provincial medical school outside of London was opened in Manchester in 1825 by Thomas Turner FRCS (1793-1873). This was at Pine Street, close to Piccadilly. Extended in 1832 and awarded ‘royal’ status by William IV in 1838, it was then known as the Manchester Royal School of Medicine (MRSM). John Dalton taught pharmaceutical chemistry there and Edward Lund taught anatomy.

In 1850 another school at Chatham Street was established. George Southam, a former Pine Street student and soon-to-be resident of Eccles Old Road, was a founder and lecturer. The Chatham Street school had a better dissecting room and library than MRSM, and the two schools merged in 1858. In 1872, the enlarged MRSM amalgamated with Owens College, later Victoria University. George Southam and Edward Lund both held posts as Professor of Surgery there.

Thus the present day Manchester University School of Medicine can date its origin to 1825 in Pine Street.

Nurse training

Until the mid 19th century, nursing was not regarded as a profession or even as a respectable activity. Female family members or domestic servants generally carried out feeding, cleaning and personal care for the sick. In the workhouses, care was often provided unpaid by the more able paupers. Treatment in hospitals was not common before 1880, by which time anaesthetics and antiseptic surgery had made hospital care a more attractive option.

The need for nursing skills and training did not start to be recognised until the Crimean War (1853-55), when Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole raised the profile of nursing. In 1860 Nightingale opened a training school at St Thomas’s in London, one of the first to teach formally both nursing and midwifery. As more training schools opened up educated women started to see nursing as an acceptable and accepted activity.

In 1864 the Manchester Nurse-Training Institution was set up, having sent four women to be trained in London. It provided both private services for those able to pay and charitable care for the poor, the one activity subsidising the other. In 1881 it changed its name to the Manchester and Salford Sick Poor and Private Nursing Institution. One of its premises was at the Queen’s District Nursing Home on Chapel Street, later the original Salford Royal Hospital.

In 1906/07 Edith Cavell was Matron of the Salford nursing home. Born in Norfolk, she went in 1907 to Belgium as Director of its first nurse training school. She was still there at the outbreak of WWI. It is estimated that during the first year of the war, she helped around 200 British, French and Belgian soldiers escape into neutral Holland. Edith was captured by the occupying German army and was executed in October 1915. Edith Cavell is commemorated in Salford on the War Memorial in Sacred Trinity Church, and in Cavell Way in Pendleton.

Some early Pendleton medical practitioners

Thomas Percival (1740 – 1804) In 1775, the road’s most eminent doctor moved into Hart Hill. He was Thomas Percival, the grandson and nephew of Warrington physicians, who took the house, ‘for the purpose of health and for the pleasure of occasional retirement’. Thomas’s own health as a child was later described by his own son as ‘feeble and precarious’, and he took a lifelong interest in researching and promoting public health.

In 1778 he sent samples of the air from both central Manchester and Hart Hill to fellow scientist Joseph Priestley. Priestley’s analysis concluded that the air quality at Hart Hill air was ’nearly the same as that of Wiltshire’. Thomas Percival studied the population and death rates across Manchester and surrounding areas. His results showed mortality rates of 1 in 28 in Manchester compared with 1 in 120 in rural Monton, just four miles away. He proposed ways of collecting more accurate population and mortality statistics and corresponded with Benjamin Franklin, one of the founding fathers of the USA, on the value of censuses.

His early work on the impact of epidemics on the health of working children influenced Sir Robert Peel’s factory reforms. The deaths from ‘Hooping-cough’ in May 1780 of two of his youngest children can only have strengthened his resolve to tackle the causes and spread of infectious diseases through improving living and working conditions and medical provision. In 1789 and 1795 typhus and typhoid epidemics hit Manchester. As a surgeon at the Manchester Infirmary, he worked with like-minded colleagues to study the living conditions of the working classes of the town and recommend reforms. In 1795, he was instrumental in establishing the first voluntary Board of Health which worked to prevent the generation and spread of infectious diseases and to shorten and alleviate the sufferings of those affected. The isolation of patients with infectious diseases was a priority for Thomas, and this was achieved first by establishing ‘Fever Wards’, designating 25 beds in four houses on Portland Street. These were replaced in 1803 by a purpose built 100 bed ‘House of Recovery’ a site later occupied by the Grand Hotel on Aytoun street.

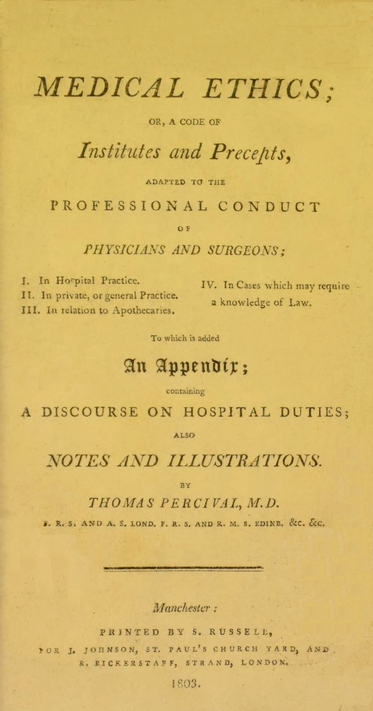

Probably the best known of Thomas Percival’s works is his 1803 ground-breaking ‘Medical Ethics; or a Code of Institutes and Precepts adapted to the professional conduct of Physicians and Surgeons.’ His last major work, this was the first codification of its kind and covered hospital settings, private and general practice, apothecaries and cases requiring knowledge of the law.

The code began as an attempt to arbitrate the difficult relationships between the various medical practitioners at the Manchester Infirmary. It was a set of rules and regulations which surgeons, physicians and apothecaries were to follow in their dealings with each other and their patients. It was also probably the first use of the term ‘medical ethics’. The work influenced the codes of practice and were eventually adopted by the British and American Medical Associations. Whilst still at Hart Hill, Thomas became afflicted with a painful and debilitating eye condition, which he attributed to his common practice of reading and writing while travelling around in his carriage. The condition was chronic and forced him to have constant assistance in all his work. It may have been for this reason that he eventually sold Hart Hill in 1783 and returned to living full-time in Manchester.

Thomas Percival died in 1804 of rheumatic fever.

George Southam (1815-1876) was not born when Percival died, but he would have certainly known of him and his work in shaping the principles and structures of healthcare in Manchester.

George was the nephew of a surgeon (John Justice Southam) and his grandfather, George, was also believed to be a medical man. His own father was a grocer and provisions dealer and, intriguingly, the official muzzler of mastiffs and bitches. He gave his son a good education, sending him to Manchester Grammar School. In the 1830s George studied medicine at the Royal School of Medicine in Pine Street, Manchester and then in London and Edinburgh.

In 1841 Pigot and Slater’s Trade Directory lists George Southam, Surgeon, living at 7, The Crescent, Salford. In 1842 he married Rebeka, daughter of Elkanah Armitage. He appears to have moved between a number of Crescent properties over the next 10 years: he is at number 4 in 1847 (Slater’s) and number 19 in 1851 (census). It was while Southam was living at the Crescent on 7 January 1857 that he was called upon to certify the sudden death of Salford’s MP Joseph Brotherton. National and local newspapers reported the dramatic event:

THE LATE JOSEPH BROTHERTON, ESQ., MP

Joseph Brotherton, Esq., the parliamentary representative for Salford died suddenly on Wednesday forenoon, in an omnibus while proceeding from his house in Pendleton to fulfil an engagement at Manchester. Besides Mr Brotherton there were also in the omnibus at the time Sir John Potter, and Sir Elkanah Armitage, two of his most intimate friends. He sat opposite to these gentlemen , and joined freely with them in conversation. When they had reached Albion Place, Sir John Potter’s attention was attracted by a sudden change in Mr Brotherton’s expression of countenance and he remarked the circumstance to his brother alderman (both Sir John and Sir Elkanah are aldermen). The remark had scarcely been made when Mr. Brotherton sank backwards on the seat he occupied, his eyes becoming fixed and glassy. They spoke to him but he never answered; and, although his eyes moved upwards two or threee times before they finally closedx in death, there is every reason toi believe that he died almost at the very instant his illness was first observed. The omnibus had by this time proceeded about 150 yards after the alarming symptoms were first noticed, and it was now nearly opposite the residence of Dr G Southam, surgeon. Here the omnibus was stopped; and with the assistance of some of the passengers, the body was carried into Mr Southam’s house. That gentleman was at the Royal Manchester Infirmary; but his assistant, Mr Pitman, was in attendance and pronounced life to be quite extinct. Mr Southam and Mr C Harvey, also a surgeon, were sent for and soon arrived; they agreed that human assistance could not have availed to avert, even for a time, the melancholy event. The intelligence spread rapidly through Salford and Manchester, producing, as may be imagined, a painful feeling and earnest expressions of regret……….The surgeons named, from their professional and personal knowledge, the one being his ordinary medical attendant, the other a near relative, declare that the death of Mr Brotherton was occasioned by disease of the heart. The Daily Post, Liverpool, January 9, 1857

The 1858 Post Office Directory shows the Southam family, now with five children, living at the newly built house to the east of Belmont. Not yet named or numbered, by the 1861 census it is listed for the first time as No.1 Eccles Old Road. At the next census in 1871 the house is named Oakfield, and remains so for over 50 years.

George Southam served the people of Salford and Manchester for almost 40 years. In 1846 he was appointed House Surgeon and later Surgeon at the Salford Royal Hospital and Dispensary. In 1847 he was appointed dispensary surgeon to the Manchester Royal Infirmary. Four years later he led the establishment of the Chatham Street School of Medicine in Manchester (at the corner of Chatham St and Grosvenor Street). An introductory lecture in and an address by Sir J Kay-Shuttleworth was given on 2 Feb 1853. The school was only the second of its kind (the first being Pine Street, where George himself had studied) and was a success, teaching anatomy and the principles and practice of surgery.

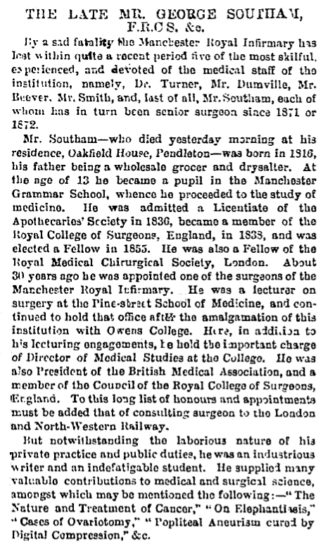

When the Pine Street and Chatham Street schools merged at Owens College, George Southam became joint professor of surgery and director of medical studies. He was a member of the Royal College of Surgeons from 1873 and president of the Council of the British Medical Association. An eminent and distinguished surgeon and academic, he published a wide range of papers, including those concerning the treatment of elephantiasis by amputation, of ovarian tumours, and on the nature and treatment of cancer.

George Southam died at Oakfield, 1 Eccles Old Road, on 24 April 1876. He was buried at St. John’s Pendlebury. The Southam medical dynasty continued when George’s son Frederick Armitage Southam (1850-1927), who had lived most of his childhood at Oakfield, also became a surgeon in Manchester hospitals, as did his son, Arthur Hughes Southam (1888-1970).

Frederick Pennington (1831-1898) Originally from Suffolk, Frederick Pennington was also a member of a medical family, his father being a surgeon. In 1881 Frederick was living at 125 Eccles Old Road. This was just beyond the Alton Terrace (now shops), before Devonshire Road. At this time, Frederick was 50 years of age and gave his occupation as Surgeon Major. He was still on the army active list and military records show that he had been a Staff Assistant Surgeon with the 9th Queen’s Royal Lancers in the mid 1850s, shortly after he qualified. During 1857-59 he had been in India and had been awarded a medal for his medical services during the widespread Indian Mutiny.

Frederick Pennington died in Switzerland in 1898. An obituary in the BMJ read:

Brig.-Surg. F. Pennington. -retired list, A.M.S., died at Lugano on 4th inst., aged 68 years. He joined the army April 22, 1858; became Surgeon March 12, 1873; Surgeon-Major April 1, 1893; and retired with the honorary rank of Brigadier-Surgeon Sept.10, 1885. He served in the Indian Mutiny, 1858-59 (medal), in the Ashanti War, 1873-74 (medal), and in the Egyptian expedition, 1882 (medal and bronze star). British Medical Journal December 12 1898

Thomas Mason Johnson (1841-1916) Born in Yorkshire, Thomas Mason Johnson came to Salford to study medicine. We find him in 1861 at 243 Chapel Street, listed as a medical student, pupil to William Crosby MRCS. The 1867 UK Medical Register tells us that Thomas Mason Johnson was working at the Manchester Royal Infirmary. He had gained his MD at St. Andrews in 1862. That same year he obtained his License from the Society of Apothecaries (LSA). A year later he was admitted as a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons (MRCS). He was a medical officer for the Salford Union.

In 1874 Johnson married the daughter of a New York bank cashier, Julia de Angelis and they were living at 251 Chapel Street in 1881 and 1891. The couple had three children, the first being William Crosby Johnson, no doubt named in tribute to his father’s mentor and partner. This son also went on to become a surgeon.

Practising as Messrs. Crosby and Johnson, Surgeons, at premises on The Crescent, there are numerous newspaper reports of their presence at incidents, accidents and inquests into local deaths.

William Crosby Johnson (1875-1952) The son of Thomas Mason Johnson, William Crosby Johnson was born in 1875 at Chapel Street. Baptised 12 June 1875, he was named after father’s medical partner William Crosby of Chapel Street. He was educated at Owens college where he qualified in 1901 with a MB and ChB. In 1902 / 1903 he was working as a Senior House Surgeon at Salford Royal and local newspapers report him giving evidence at inquests. He was also an anaesthetist at St Mary’s Hospital in Manchester.

At the time of the 1911 census, William Crosby Johnson was living at Fairleigh, 54 Eccles Old Road. For a period he was in medical partnership with Dr Alfred Williams, who in 1921 was living at Oakfield, 1 Eccles Old Road. The partnership between Williams and Johnson was dissolved in 1914. William Crosby Johnson moved to Scotland where he was practising in 1928. By 1952 he was retired in Haslemere, Surrey where he died in 1952.

John Wesley Lawton (1852-1898) General Practitioner and surgeon, John Wesley Lawton was the son of a Wesleyan Minister from Farnworth. John himself was born in Leeds. In 1891 Lawton lived at Heathmount, on the corner of Eccles Old Road and Lancaster Road, with wife Harriet Burton Lawton and two daughters Julia and Phyllis. He died 22 Jan 1898 leaving £3288.15s.7d. By 1901 his widow and family had moved across the road to the more modest 113 Eccles Old Road (now a shop). Heathmount later became the Heath Mount Hotel, then Inn of Good Hope, and by 2020 the Royal Sovereign.

Boughton Addy (1849-1918) General practitioner and surgeon, born in Lincolnshire around 1849, the son of a farmer of 132 acres. He attended a boarding school in Grantham before studying medicine in London.

Addy worked as a physician’s assistant and then house physician at the Manchester Royal Infirmary. He was honorary medical officer at Pendleton Dispensary, Salford Royal Hospital, and Vice-president of the Manchester Clinical Society.

In 1881 he was living at 13a Eccles Old Road, also called Thornhill. This was a house built at the front of numbers 13 and 15, now the Pendleton Bowling Club. Later that year, he married the daughter of a Salford coal merchant who lived on The Crescent. Ten years later, Boughton Addy was in partnership with Dr Philip Worley, with their surgery at Thornhill, although by this time, Addy was living further west along Eccles Old Road at no 29 in a group of houses known as South Bank.

Local newspapers tell us little of Boughton Addy’s life outside of his medical practice, other than his memberships of the Manchester and Liverpool Banking Company and of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. Sometime after 1891, Boughton Addy moved south to Kent and then to Surrey, where he died in 1918.

Alexander Stewart (1855-1917) Born in Scotland in 1855, Alexander Stewart was a qualified surgeon and registered general practitioner by the age of 26. In 1881, married to Florence Shaw, he was living at 60 Broad Street. Within 10 years he had been widowed and moved by 1891 to 27 Eccles Old Road, next to Dr Boughton Addy.

In 1891 he had married Constance Blanche Schwabe, daughter of Louis Schwabe of Hart Hill. They had two sons, Kenneth Alexander (a cotton merchant) and Hugh Louis Garth (bank clerk in 1911), and two daughters, Margaret Blanche and Constance Olga. At the time of the 1901 and 1911 censuses, Stewart was living on the northern side of Eccles Old Road at a house known as Laurel Bank or Laurel Mount.

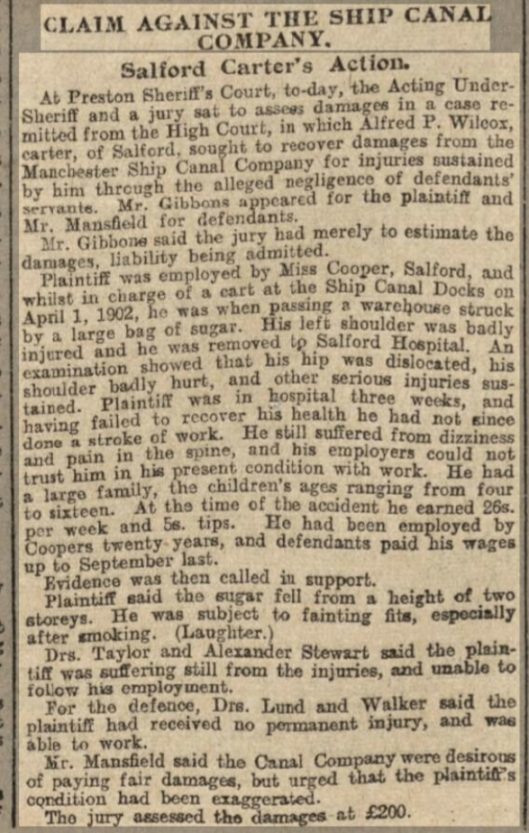

Not a great deal is recorded of Dr Stewart’s work, although a report in a local paper in 1903 did cover a court case where he and his neighbour, fellow surgeon Herbert Lund, were on opposing sides of a claim for damages against the Manchester Ship canal Company. An injured carter had been struck by a large bag of sugar and was hospitalised for three weeks. Dr Stewart supported the plaintiff, who was awarded £200 in damages.

Herbert Lund (1858-1938) Born in Whalley Range, his father was the surgeon Edward Lund FRCS, Professor of Anatomy at Manchester Royal School of Medicine. In 1889 Herbert Lund was appointed Assistant Surgeon at Salford Royal Hospital and worked there until he retired as Consulting Surgeon in 1918. He was also surgeon to Hulme Dispensary, and president of the Manchester Clinical Society. During the first world war he was a captain with the Royal Army Medical Corp, and was attached to the Manchester headquarters of the 2nd General Western Hospital. After the war he became medical referee to the Salford War Pensions Committee.

In 1891 he was living at St John Street and by 1901 he was at Fern Hill, on the corner of Chaseley Road and Eccles Old Road. He was warden of Christ Church around 1915. Herbert Lund lived at Fern Hill for around 40 years, dying there on 8 February 1938. His obituary in the British Medical Journal rather unkindly compared him to his father:

Of a retiring disposition, Herbert maintained with less brilliance the position held by his father in the surgical world of Manchester.

BMJ 1938, 1, 490

Philip Worley (1868-1942) Surgeon and GP. At the time of the 1891 and 1901 censuses Philip Worley was living and working at Thornhill, 13a Eccles Old Road. He was in medical partnership with Dr. Boughton Addy as Addy and Worley, Surgeons.

In 1904 at the baptism of his daughter Violet Olive, his address was West Hill, Eccles Old Road. West Hill may have been a later name given to 13a, or possibly to part of no. 15 Eccles Old Road, otherwise known as Belmont.

1911 and 1921 Worley was living at Hope House on the west corner of Eccles Old Road and Wilton Road. In 1918 his son, Philip Brian Worley was killed in Belgium, his army records giving his address as Hope House Eccles Old Road.

The whole section of Eccles Old Road between its start at the Woolpack Inn and Buile Hill was a popular location for the homes and practices of many of Salford’s medical establishment. During the 1930s, 4 Halton Bank was occupied by Dr. Brian Arthur McCubbin, Physician and Surgeon, 6 Sorrell Bank by Dr. Thomas Hamilton Thomson, Physician and Surgeon and 8 Sorrell Bank by Norman Harbinson, Dental Surgeon.

Charles Edward Paget (1858-1927) was from a family of eminent doctors, being the son of Sir George Edward Paget MD and nephew of Sir James Paget (after whom Paget’s Disease was named). In 1891 he lived at North Bentcliffe, Gilda Brook, later known as 137 Eccles Old Road.

He was Medical Officer of Health for Salford from 1889-1897. As President of the North West Branch of Society of Medical Officers of Health, he delivered a presidential address on ‘Some Imperfections of Public Health Administration’. Whilst in post at Salford he published in 1891 a Special Report on the Recent Prevalence of Diptheria and in 1893 a Special Report on the Prevalence of Smallpox during the years 1892-1893. These two reports are available in the Salford Local History Library.

Charles Paget was in post when the Salford Infectious Hospital was built at Ladywell on Eccles New Road in 1890. In a letter to the British Medical Journal, he corrected an article that the journal had published, and explained that the £50000 cost of the hospital would provide 184 beds, including two isolation blocks with 20 beds in each.

Charles Paget left Salford in 1897 to take up a post of Medical Officer of Health in Northamptonshire, where he died in 1927. His son, George who had been born at North Bentcliffe and baptised at St James, Hope in 1891 was one of the early casualties of World War I, killed at the Battle of Aisne in September 1914.

Egerton Allen Ferguson (1879-1948) was a Canadian physician and surgeon who lived from at least 1939 to his death in 1948 at The Poplars 162, Eccles Old Road. The property still stands today as no. 219 and is the most westerly of a pair of Victorian semi-detached villas built around 1870.

Ferguson and his wife were from Ontario, arriving around 1925. They appear to have lived first in Liverpool in the early 1900s, where he was initiated as a a member of a Freemason’s lodge in 1905. From around 1929 to 1935 he was at 90, Fitzwarren Street in Salford. In 1940 he had a practice at 194 Langworthy Road.

His son Joseph Haycock Ferguson trained as a doctor at Manchester in the early 1930s. He married a fellow medical student and they had a joint GP practice on Bury Old Road, before moving to the Isle of Man.

Annie Amelia Hipwell (1885-1985) was born in Oldham. At 22, she married Edward Jones at St Catherine’s, Barton. On the 1911 census, she was working as weaver of cotton shirting. Annie changed her life over the next 10 years and in 1921 she qualified as an enrolled midwife, living at 44 Gilda Brook Road. Ten years on, the register of midwives lists her at 2 Half Edge Lane. From 1932 until at least 1944, Annie is at the Cleveland House Nursing Home, on the corner of Eccles Old Road and Lancaster Road. The 1939 Register* lists Annie with her first husband Edward Jones. She is described as Midwife Matron.

*The 1939 Register of Great Britain and Northern Ireland was taken on 29th September 1939, on the outbreak of World War II to facilitate the issuing of Identity Cards and rationing . Since the 1931 census was destroyed during the war and the 1941 census was never taken, the 1939 Register was an important record and was used after the war in the establishment of the NHS.

In 1933 Annie’s daughter, Lilly Jones (later Jackson), qualified as a nurse at Pendlebury Children’s Hospital whilst living at Cleveland House. Annie Jones, worked towards the end of her career at the Clarendon Nursing Home in Eccles, another maternity home. She is listed there on the 1955 register of midwives. It appears that retirement took her to Birkenhead. Sadly, she was widowed three times, dying herself at the good age of 99 years in 1985.

From 1939 to 1949 Manchester Evening News family notices announced over 500 births at the Cleveland Nursing Home. Many living Salfordians may well have been delivered by Annie Hipwell.